Scientists have discovered a host of genetic factors that predispose people to heart attacks, in the largest medical study of its kind.

The investigation has already helped researchers tease apart the complex biology of coronary heart disease, the most common killer in Britain and elsewhere in the developed world. The work is expected to provide new clues for developing drugs to prevent heart disease and paves the way for a genetic test that can predict a person's risk of suffering a heart condition later in life.

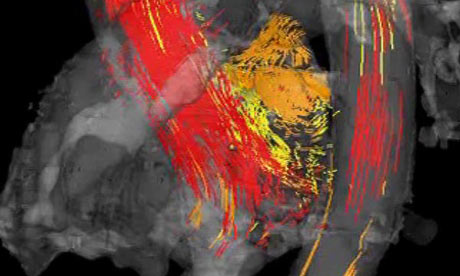

Scientists took blood samples from more than 100,000 people and measured the amount of fat in their circulation, in the form of cholesterol and triglycerides. They then screened the participants' DNA to look for genetic factors that influenced their blood fat levels.

The body needs cholesterol and triglycerides for energy and to build cell membranes, but too much or too little can cause serious health problems. Cholesterol comes in two forms: bad cholesterol (called LDL for low-density lipoprotein) builds up inside arteries and causes heart disease, while good cholesterol (called HDL, for high-density lipoprotein) removes fat from arteries and moves it to the liver. Around half of a person's cholesterol and triglycerides are hardwired by genetics, with the rest depending on diet, exercise and other lifestyle factors.

The study, reported in the journal Nature, found 95 genetic variants that raised or lowered levels of good or bad cholesterol and triglycerides, 59 of which were previously unknown to scientists. Almost all of the genes affected blood fat levels in Europeans, Africans and Asians. Further tests showed that 13 of the gene variants were directly linked to a greater risk of heart disease, with most doing so by raising levels of bad cholesterol in the blood.

"We're essentially finding genes that govern lipid levels in people's blood. By identifying these genes, we might be able to find drugs that can help, perhaps by lowering levels of bad cholesterol," said Sekar Kathiresan, lead author on the study and director of preventative cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Taken together, the 95 gene variants explain a quarter to a third of inherited cholesterol and triglycerides levels. The remaining 75% is almost certainly governed by rarer genetic variations.

In a second paper, another team investigated one of the gene variants in detail and unravelled how it altered the production of bad cholesterol in the body. Researchers now plan to investigate how the rest of the gene variants affect fat levels in the blood.

"Genetic studies that survey a wide variety of human populations are a powerful tool for identifying hereditary factors in health and disease," said Francis Collins, a co-author of the study, director of the US National Institutes of Health and former leader of the Human Genome Project. "These results help refine our course for preventing and treating heart disease that affects millions of Americans and many more people worldwide."

In Britain, heart attacks and coronary disease kill roughly 190,000 people each year and account for a third of all deaths.

Dr Kathiresan said one future goal was to develop a genetic test to predict a person's risk of high cholesterol before they reach middle age. Such a test could feed into doctor's advice for patients on improving lifetstyle and lead to better prescribing of anti-cholesterol drugs, such as statins. A test would have an advantage over blood tests of revealing a patient's inherited risk of heart disease.