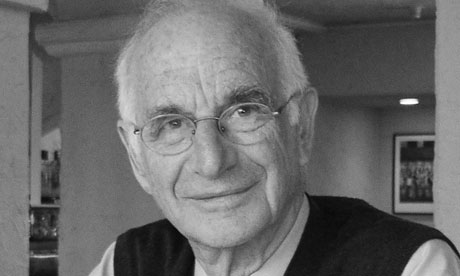

James Hillman, who has died aged 85 from the complications of cancer, has been hailed as the most important US psychologist since William James. He was a dedicated subversive – witty and original – and an heir to the Jungian tradition, which he reimagined with unceasing brilliance. Fiercely critical of America's dedication to the pursuit of happiness, Hillman focused on the darkest and most difficult human experiences – illness, depression, failure and suicide – not merely as abnormal pathologies that should be avoided or cured.

He drew on the writers and philosophers of the Italian Renaissance and ancient Greece, as well as a romantic tradition that included Keats, Goethe, Schelling and Dilthey. Not wishing to create a school of his own, he proposed an "archetypal" or "imaginal" psychology that would restore the psyche or soul to a discipline he believed to have been diminished by scientific and medical models. Influenced by the French Islamist and Sufi Henry Corbin, the poetics of Gaston Bachelard and the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, he argued that reality is a construct of the imagination – the stuff of myths, dreams, fantasies and images. There was, however, very little about his thought that was divorced from the world of money, war and politics. His unrelenting cultural critique embraced everything from masturbation to plastic surgery, and the design of ceilings to US foreign policy.

The "image" as an expression of the imagination, in poetry, dreams or visual art, was of paramount importance to him – as an antidote to the literalism that dominates everyday discourse. Hillman warned against the reductive tendencies of interpretation and theoretical speculation. He would advocate "sticking to the image", whose often indistinct or paradoxical language spoke, he argued, with more authenticity than verbal discourse. Film was an ideal vehicle for his ideas. He was the main contributor to my films The Heart Has Reasons (Channel 4, 1993), Kind of Blue (Channel 4, 1994) and the five part-series The Architecture of the Imagination (BBC2, 1994).

Hillman drew on pre-Christian modes of thought – a polytheistic perspective reflecting the myriad possibilities of the human psyche, imagined as gods and goddesses, myths and metaphors whose polymorphous nature spoke for the instincts that shape our thoughts and actions more truthfully than the good-and-evil world of oppositions central to the monotheistic religions of the book.

Hillman grew up in Atlantic City, New Jersey, with parents in the hotel business – they partly owned the George V in Paris. In a seaside resort that sold and lived by illusion, he spoke of learning early on about things not always being what they seemed. During the second world war, he served in the US Navy Hospital Corps, looking after blind people – an experience that exposed him to the sightless patients' rich inner life, as well as convincing him of the pitfalls of institutional medicine.

After studying at the Sorbonne and Trinity College, Dublin, he travelled in Africa and spent a year in Kashmir, where he discovered the writings of Jung. He returned to Europe to work on a PhD at the University of Zurich and enrolled on a diploma course at the Jung Institute in 1950. Soon after qualifying, he became director of studies, remaining there until 1978.

During this time he published groundbreaking works including Re-Visioning Psychology (1975), based on the prestigious Terry lectures he had given at Yale in 1972. This Pulitzer-nominated book was followed by The Dream and the Underworld (1979) and The Myth of Analysis (1983). In these central studies Hillman set out, with great erudition as well as a gift for subversion, to "see through" the idea and practice of psychology, the way in which we extract meaning from dreams and the guiding fictions behind the practice of psychoanalysis.

Hillman left Zurich to become graduate dean at the University of Dallas, where he remained until 1984, and where he also set up the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, which fostered the radical appraisal of cities and our lives within them. He also edited the journal Spring and was chief editor of Spring Publications.

Having practised as an analyst for 40 years, he eventually became highly critical of therapy. He argued that the sickness of humanity lay in the world rather than within each person. Therapy should, he believed, change politics, cities, buildings, schools and our relationship with the natural environment rather than focus solely on people's inner lives.

Although far from sympathetic to its sugar-coated promise of wholeness and fulfilment, he was co-opted by the New Age movement, always anxious to promote gurus with a fresh message. He came dangerously close to being identified with it when he was, for several years, involved in the men's movement, alongside the poet Robert Bly and the social activist Michael Meade.

He moved on to find a wider audience through a series of popular but still provocative books, including The Soul's Code (1997), which reached No 1 on the New York Times bestseller list, and The Force of Character (1999), works which explored, with examples running from Picasso to Hitler, the idea that we all have a calling, an individual and innate character which shapes our lives. In A Terrible Love of War (2004), he reflected on humanity's abiding martial ardour and need for the periodic spilling of blood, at great cost and with incalculable suffering.

As well as writing beautifully – texts of layered intellectual exposition that were dense yet always skilfully articulated – Hillman was an electrifying lecturer and teacher: a tall and charismatic mixture of rabbinical scholar and comedian, with a breathtaking ability to lead his audience through arguments that turned accepted ideas upside down. Unlike other critics of the mainstream approach to mental illness, he was not "anti" anything, seeing in opposition a fantasy that drew us away from meaning and from life. He preferred to deconstruct, often playfully, whether he was speaking of plastic surgery, the politics of the Middle East or the paranoia of the psychiatric profession.

Not surprisingly he approached death, through a period of great physical suffering, with courage, humour and a continuing curiosity about the fictions that surround our ideas of life and death.

He is survived by his wife, Margot McLean, and his children by his first marriage, Julia, Carola, Susanne and Laurence, and five grandchildren.

• James Hillman, psychologist, born 12 April 1926; died 27 October 2011