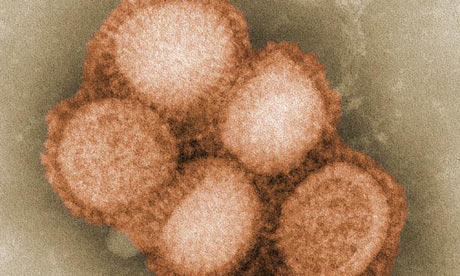

Inside Department of Health headquarters in Whitehall, two words dominate: swine flu. Every day brings a flurry of discussions about how to react to the rising number of infections, sifting of the latest statistics, analysis of how to explain things to a worried public and, crucially, what the NHS should be doing if things get a lot worse, as most experts believe the pandemic will.

Much of the intelligence about the virus comes from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, a 20-strong committee of scientists which has been established to give ministers and civil servants the best possible information about the flu pandemic's development.

Every few days, they meet senior health department officials who are playing the lead role in tackling swine flu. They include Professor Lindsey Davies, the director of pandemic influenza preparedness; Roy Taylor, the national director for social care flu resilience; and Ian Dalton, the national director for NHS flu resilience. Having prepared how to react to a theoretical pandemic, they are now doing their utmost to minimise the effects of a real one.

Already more than 10,000 people have been confirmed with H1N1, although some experts believe the real infection rate is probably six or seven times that. The death toll has reached 16, the latest being six-year-old schoolgirl Chloe Buckley from north-west London. Her death, announced on Monday, has increased public anxiety because she appeared to be healthy before contracting the virus, unlike many of the other fatalities, who had underlying medical conditions that left them more vulnerable.

The nuances of the Department of Health's message to the public on swine flu are vital. In the department's press office, a team of officials deals with media inquiries about nothing else. When the health secretary, Andy Burnham, or the chief medical officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, discuss swine flu publicly, they try to be calm and reassuring and are keen to reinforce public health messages, such as the need for people to wash their hands regularly.

Asked about Chloe's death yesterday, Burnham said: "There have been lots of children already having the condition but making a very quick and full recovery. We do have to keep it in perspective."

A Department of Health spokeswoman said the tactics on swine flu had not changed since Burnham made his last major statement to parliament on the pandemic on 2 July. No change in policy was expected soon, she said. "The deaths are sad. But I want to reinforce to the public that in the majority of cases it's proving to be very mild, and a lot of children who have the virus have recovered."

Dr Mike Skinner, a senior lecturer in virology at Imperial College London, endorsed the department's stance. "We had been warned that there would be relatively small numbers of deaths. It is a feature of this virus that about 20% of the deaths are likely to be in people who were otherwise healthy," he said.

However, the NHS is preparing to cancel non-emergency operations, discharge patients early and care for people with swine flu miles away from their homes if hospitals become overwhelmed with people who are seriously ill with the virus.

Donaldson said last night on Newsnight that authorities were looking at a number of ways to lessen the burden on doctors as the number of cases rise, such as speeding up the process by which death certificates would be issued.

The department of health has agreed a number of contingency measures with local NHS leaders during efforts intended to help them prepare for a possible huge increase in the number of people who need what would in some cases be life-saving treatment.

Operations involving elective or non-urgent surgery for conditions such as a hernia or varicose veins would be halted and beds earmarked instead for people whose health is at risk because they have swine flu as well as breathing conditions such as asthma, bronchitis or pneumonia.

Hospitals in swine flu hotspots such as London and the West Midlands which could become overwhelmed by the number of patients also have plans to transfer some to other hospitals which could be 10 or 20 miles away. A serious outbreak of swine flu in Telford and Shrewsbury, for example, could see patients with complications linked to the H1N1 virus being taken to hospitals in Stoke and Wolverhampton.

Plans to "share" patients between neighbouring hospitals have been agreed in talks involving strategic health authorities, primary care trusts, individual hospitals and Dalton, the director for NHS flu resilience.

Hospital doctors who usually practise other forms of medicine will also be expected to help colleagues in acute and intensive care medicine deal with a potential upsurge in swine flu patients. For example, West Essex primary care trust has set out plans to deal with what it called "surge demand". It expects that if a dramatic increase in the number of people with swine flu produced 1,200 more hospital admissions a week than usual, some 300 of them would require critical care. That, it says, would involve the "prioritisation of health services [and a need to] decide on essential and non-essential services in a graded way, in order to free up capacity.

"All parts of health and social care have to prepare themselves for the surge in demand they might experience and have to decide on essential and less or non-essential services within their service," the West Essex primary care trust said.

A briefing it produced says if the number of cases rises sharply, "hospitals should be able to increase (to double) the availability of critical care and significantly increase the number of acute care beds in 48 to 72 hours. About a third of acute beds can be released within 10 days of a decision being made to cease elective surgery.

"It is possible that increasing capacity and prioritising services will not meet the need during a peak pandemic period, in which case demand control measures will be required (eg, rapid early discharge)."

Professor Steve Field, chairman of the Royal College of General Practitioners, praised the NHS for being clear and realistic in its advanced planning for a worst-case scenario. "There are robust plans in place in all hospitals to manage any increase in the number of patients with influenza and an increase in patients who have respiratory illnesses, such as pneumonia, bronchitis or asthma.

"As the numbers increase, a proportion of those will inevitably need intensive care, as some swine flu patients are already getting. These plans will include the use of hospital beds, the postponement of elective surgery, the use of surgical beds and the sharing of patients between hospitals which, if it got very severe, could see some patients moved out of their locality."

Scientists on the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies committee believe that all possible steps are being taken. A senior adviser said: "The UK is doing extremely well."

But not everyone is convinced. Andrew Lansley, the shadow health secretary, has highlighted the delay in establishing the proposed national flu line, which the Department of Health agreed in January was a necessity. That is intended to be a new service to which patients can turn if and when GPs can no longer cope with huge numbers of sick people.